Ads used to be here |

|

|

An

Interview with

C.Y. Lee The Literary Legacy of C.Y. Lee by Lia Chang |

||||

|

||||

|

C.Y Lee, the 85-year old bestselling author of The Flower Drum Song is enjoying an auspicious revival in the sunset of his life. In many ways, it is a new beginning. Chin Yang Lee, the youngest of 11 children was born in the Hunan Province of China in 1917. He escaped China in 1943 during WW II on a student visa first studying Comparative Literature at Columbia University, and then transferring to the Yale Drama School to study playwrighting.

Encouraged to try his hand at fiction, after graduation he worked as a social news editor and entertainment reporter for Chinese World and Young China in San Francisco's Chinatown by day while writing his novel The Flower Drum Song at night. The novel was published in 1957 and became a New York Times bestseller. The astute portrayal of Chinese American life in San Francisco Chinatown with authentic characterizations of Chinese American men and women was a rarity at the time. Librettist and Gentleman Prefers Blondes screenwriter Joseph Fields optioned the novel and convinced Rodgers and Hammerstein to create the musical stage version of Flower Drum Song with Gene Kelly as the director. Opening at the St. James Theater in December 1958, with Pat Suzuki and Miyoshi Umeki, the musical was the first show to focus on the Chinese American experience, starring Asian Americans on Broadway. In 1961, when the film adaptation was released, it became the first major Hollywood studio film about and starring Asian Americans, launching the careers of the first generation of Asian American stars -- Miyoshi Umeki, Jack Soo, James Shigeta, and Nancy Kwan. In the early 80's, as Asian American Studies classes were created in colleges across the country, The Flower Drum Song was not included in the developing Asian American Literary Canon. Dismissed by activists and Asian American studies scholars for perpetrating stereotyped clich�s of Asian Americans, subsequently, his other 10 novels were disregarded as well. When Tony Award-winning playwright David Henry Hwang decided to rewrite the book for Flower Drum Song and try to bring it to Broadway, he felt he needed to return to the source for inspiration. Obtaining a rare used hard copy of the novel from David Ishii, a bookseller in Seattle, Hwang was entranced by what he read and went in search of the author. Through the valiant efforts of Hwang, Flower Drum Song is back on Broadway, and 45 years after The Flower Drum Song first became a New York Times bestseller, it is back in print, reissued by Penguin Books. In addition, Hwang has lobbied Asian American studies programs across the country to include The Flower Drum Song as required reading. Enlightening Noah Publishing Co. in Santa Clara, CA has published all ten of Lee's novels in Chinese and the C.Y. Lee Archive can be found at Boston University's Mugar Memorial Library. By a stroke of good fortune, I encountered C.Y. Lee with his daughter Angela, a TV and film producer and his son Jay, a filmmaker, outside the Virginia Theatre on the opening night of the new Flower Drum Song on Broadway. Four days later, the novelist agreed to sit down for a chat.

Angela graciously invited me to visit with her and her dad over a Chinese dinner in her spacious East Village apartment. Dressed in a plaid shirt, his favorite red sweater and khakis, the pioneering literary spirit has a devilish twinkle in his eye, a love of ballroom dancing and women. A gifted storyteller, C.Y. engaged me with his early years as an entertainment reporter in San Francisco, his inspiration for writing The Flower Drum Song, the first of his 11 novels, anecdotes from the original 1958 stage production, his unique connection to David Henry Hwang and the latest details on his memoirs. Lia: How did you end up in journalism? C.Y. Lee: I came to this country without thinking I would go into journalism at all. When I finished Yale, I went back to Los Angeles, ready to go home. Some people told me, "Let them deport you, you don't have to buy a steamship ticket." So I relaxed. My money ran low. Somebody told me in Chinatown, there's 25 cents a bowl of noodles. So I went to Chinatown to eat that 25 cents noodles with free tea and free newspaper. The newspaper is from San Francisco called Chinese World. They are trying to publish English version. They had a little note saying we are trying to hire a columnist writing in English. I wrote three articles and sent to the paper. A week later they said all right. The editor said, "I'll pay you five dollars a story. We need five articles a week." I counted on my fingers; it was a lot of money. I could buy a lot of noodles. I took the job. And sometime later, the editor said, "Since you are bilingual, you might as well come work for the Chinese section also. You translate interesting stories from San Francisco Chronicle and San Francisco Examiner, for the Chinese section. It was a very good job for freelance writers. Because they supply three meals, they supply room upstairs, and they said if you want to keep your job we can supply a coffin. That gave me a lot of security. You don't have to worry ever, not to even buy a coffin. Naturally I just liked the meals. I refused the room and refused the coffin. I refused the room; I don't want to live here. Just eat your three meals a day, I would be very happy. That's how I forced myself to get into journalism. (laugh) Lia: What were your roles in the newsroom? C.Y. Lee: The newsroom, those buildings, they have three stores; the newsroom was the second store. And the dormitory was the third store. The newsroom was a big office. Everybody works there. Editorial department and the other department were very noisy. I had my own desk close to Grant Avenue. With Grant Avenue's noise and the manager's voice (the manager's Cantonese who also owns a teahouse)-he's giving orders to the reporters and giving orders to the staff at the teahouse. He's constantly yelling in the telephone. As a result it was terribly noisy. It's a good thing; I trained myself to concentrate in writing. To shut off all the noises. That's a good thing for me. I concentrated writing the Chinese and the English column. I was a reporter but I never interviewed anyone. The Chinese papers somehow didn't interview people in those days. I was translating social news. Of course it was very important news. I wasn't an editor of the paper. I was a translator, a social editor because I select the social news. Since it is for entertainment purposes, its not accurate. I added a lot of spice even invented a little scandal. Entertainment reporter of course. Lia: Where were your offices located? C.Y. Lee: I worked for two papers-Chinese World on Grant Avenue, Young China on Sacramento St. Lia: How many reporters were in your newsroom? C.Y. Lee: We don't have reporters because they are so poor, they don't hire reporters. You translate from English to Chinese. All the Chinese community information is sent to the paper. Family associations sent their reports to us to be printed. A lot of funerals, weddings. The paper gets advertising not from a lot of merchants but instead from people who died or with weddings. Free advertising for weddings. Free advertising for funerals. You know, funerals to Chinese are very important. The paper informs everybody so and so died. The children, filial piety, they print all the names. Sons, daughters, grandsons, the bigger the better. To show whose family has the biggest family. Lia: Can you describe the coverage of the mainstream of Chinatown at that time? C.Y. Lee: Mainstream coverage. Both newspapers were for the elderly generations because the young generations don't read Chinese papers. So for elderly people, we call it big letter newspaper, big words. So old men can read it more easily. And I know they are interested in social stories, anything about scandals, murders. And if we have Chinese scandals, they really wanted it. But Western papers, rarely published Chinese scandals, Chinese have a saying: ugly family scandals should never be exposed to foreigners. This is the rough translation of the Chinese saying. since I tried to be a fiction writer, I never checked accuracy. I sometimes invent some stories. Lia: What type of coverage did you try to offer about Chinatown and about the mainstream? C.Y. Lee: I was interested in writing my own story. I was trying to write fiction, and with fiction, there are two things you have to find. One is the basic conflict. The other is the character. That is very important. Without it, there is no story. But in Chinatown, I discovered the generation gap is the main conflict. And the older generation, the younger generation they have this cultural conflict. That's the conflict we always have, not just in Chinatown, even in China we have that conflict. Lia: What inspired you to write The Flower Drum Song? C.Y. Lee: Because I think working for that kind of newspaper, naturally you don't want to die there and use their coffins. From the very beginning I tried fiction. Three pages of fiction saved me. I have immigration problems. When you finish school you are supposed to leave. One day I got a phone call. I thought it was immigration. And I said officer, "I'm packed. Deport me anytime." And he didn't understand me. It turned out he was the editor of Writer's Digest. He said, "You have won the first short, short contest." The title of the story was called the Forbidden Dollar. He said, "You won $750 dollars. Ellery Queen Magazine bought the reprint rights and paid $750 dollars. We have a $1500 check for you plus a certificate, award certificate." He was calling to make sure I am the right person and then he would send it. When I received these things, I took them to the immigration office to get an extension. I never thought of trying to get a permanent residence, but they gave me the permanent resident's application. That's even better. You apply for that; you will be able to stay for 5 more years. In the end of 5 more years, you will be able to become a citizen. That's even better. Money in one hand, immigration papers in the other, happily settled down and tried to write my fiction. That's how I started writing The Flower Drum Song. I learned how to start a novel. Basically find a conflict. That conflict I already discovered, the generation gap. And the characters are all composite. When you write fiction, then you have to use everybody. Your friends, yourself, your family. I put everything together, slowly, without worrying about immigration, without worrying about meals. I started writing. Lia: How did you find a publisher for The Flower Drum Song? C.Y. Lee: When I finished the novel, I sent it to my agent, Ann Elmo in New York. She read it and said, "All right, I'll handle it." She sent it out for almost a whole year. She told me it was rejected by most of the editors. There's one more publisher, Farrar, Straus & Cudahy. -We called them highbrow publishers. She said, "Let's send it. If they return it you might as well think of another line of profession." She hinted that. I said all right. It was a turning point in my life. It was a little strange to me. In the very end, it was almost like the whole thing was a loss. If it wasn't so, it meant getting out of the writing profession or get out of the country. I thought about it. But as it happened, the book landed in the hands of a reader. The publisher hired readers to screen novels. My book landed in the sick bed of an eighty year old man. He didn't have the energy to write a critique. And he just wrote two words, "READ THIS" -- and died. That, my publisher John Farrar told me himself. That's a strange thing. If it landed on somebody else's desk, or bed, he might not like it. That's the end of my novel. It might never have gotten published. John Farrar would never read anything the screeners would say was no good. That's good. The major partner, John Farrar read it himself. And he liked it. But he didn't like it so much that he would say, "Oh I am excited about this novel." He just told my agent, "This novel is quaint and episodical. It may not have a big market but because there is some sparkle in his writing, I would like to buy this first one in order to read the next one." Publishers, even today, have a clause in their book contracts -- the First Refusal clause. Whenever they buy the first book, they have the first refusal. Lia: Why do you think it became a best seller? C.Y. Lee: The funny thing is that a lot of other publishers refused it because it was quaint and episodical. The New York Times liked it because it was quaint and episodical. Lia: What do you think was the secret of your success with the novel? C.Y. Lee: The secret is this, if you have found the conflict and interesting characters, you have to write for American mainstream readers. Mainstream readers would like to look into a window and see something fresh, they have never known before. I write this book, it's a Chinese life and this Chinese life is different from the White Man. Usually the white writers they stereotype Chinese, so as a result in those days the general public only see Chinese as kind of a timid fellow bowing all the time, walking with their hands in their sleeves, and some even think Chinese are still wearing pigtails in China. Women have small bound feet. It is all stereotypes. Speaking pigeon English. Suddenly they saw a new book with ordinary people. Acting like Americans, human beings, mannerisms and costumes are a little different. So they discovered that and they liked it. Rodgers and Hammerstein discovered that they should put it on the stage. They also claimed that they know the stereotype would never correct the image unless they do something about it. So Rodgers and Hammerstein did something about it. Also, you should use Asian to play Asians even though you couldn't find some Asians and they still finally used Asians later. In the beginning, in the stage version, they couldn't find, so they used a couple of Caucasians and the one black woman. Finally in the movie they got rid of the Caucasians and Juanita Hall, the black woman, looked Asian, talked and behaved normally. So this was something new. David Henry Hwang discovered in those days, he was little, he said I would never read books about China, or saw movies about China because they were too stereotyped. He hated it until he saw Rodgers and Hammerstein's Flower Drum Song musical and later on read my book. So he was determined to rewrite it. Lia: How did you find some of the actors for the 1958 cast? C.Y. Lee: That's what Gene Kelly asked me. Where would he find Asian Actors and performers? Traditionally, Chinese don't want their children to go into performing arts. In short, they don't want them to go into the arts, including writing. Very difficult to find Asians in the performing arts. Gene Kelly is very anxious too. He was the stage director. He asked me. I told him there was this one place, a honky tonk place catering to sailors. Do you mind to go? Sure we'll go. So we went there and he saw a comedian he liked. And after the show he invited the comedian to his table and he asked if he would like to go to Broadway. Jack Suzuki was a Japanese Comedian pretending he was Chinese. Jack said, "Who doesn't? When? I'm going to resign right away and go with you." Gene Kelly said, "On one condition. You have to change your Japanese name to Chinese." Jack said, "You got it right away. At this moment I become Chinese -- Jack Soo." That's how Japanese comedian became television star, Broadway star, film star. The show accepts Asians to play Asian. Somehow Gene Kelly wants Chinese playing Chinese. I'm glad he did. I'm proud of turning a Japanese comedian into a Chinese Star! Lia: What can you share about Pat Suzuki who played the original Linda Low on Broadway? C.Y. Lee: She's very good. She sings very well. I had a job writing a script for Twentieth Century Fox. Anxious to go to New York, R&H Company started rehearsing at the St. James Theatre. I was itching to come to watch the rehearsal. I came to New York, the first thing I saw as I walked into the St. James Theatre, Pat Suzuki was rehearsing I Enjoy Being a Girl. I was really moved to tears.

Lia: What was it like to experience the two different Flower Drum Songs? C.Y. Lee: The second one is a surprise. Because the book and the musical were almost dead after 30 years. The book was out of print for many many years. And suddenly David wrote me a letter saying that he would like to try to rewrite the musical. And I thought the book was almost like an old lady, dormant. I didn't think it was dead; eventually I might have it revived somehow in Chinese. You cannot beat a dead horse alive. David suddenly comes-I visualize a man on a white horse and he came and picked up the dead body and revived him and rode into the sunset. Like the lovers. The play, the show and the book become like lovers. It somehow looks like it. That's a surprise to me. I discovered when I moved to San Gabriel Valley, the Chinese community. A lot of younger people. They never heard of Flower Drum Song. Especially those who don't speak English. And so the Chinese community in those days, they never really advertised for the Chinese community Flower Drum Song. In those days, only the mainstream learned about Flower Drum Song, Chinese didn't. This time luckily, here in New York, the Chinese community discovered it. This time we have Chinese community activities. And I am very happy about this. Lia: How would you compare your novel with the two different productions? C.Y. Lee: I thought because I studied playwrighting, it is very difficult to use a novel to write a screenplay or a stage play. A novel is so huge in scope, you go to people's mind and you extend the time and the ages. The reader can pick it up and read it the next day or next week and they don't have to rush to finish it. But on stage you have two hours. You have to use the material and finish it in two hours. Have this conflict, have the character, and another idea is not to insult the Chinese. So based on this, David, even Rodgers and Hammerstein version did that. They use the conflict even though they complicated the love story. They made it more entertaining but still revealed the conflict. But my conflict was a little bit complicated here and there. For instance in the novel, the old man didn't believe in bank, the old man didn't believe in western medicine. Tiny conflicts, in the novel, you can describe it, but for stage you have to really concentrate in two hours and show the conflict. David used the Chinese Opera to represent the Chinese tradition and the young son used the nightclub to stake his claim as an American. These two are symbolism to show the conflict. I am very satisfied about it. As for the relationships, my idea is to reveal the Chinese Family members. They are concerned with each other, but because of the conflicts, they create problems with the younger generation. For instance the father is very angry, when the son walks out, but is immediately worried about how he's going to make a living. This indicates their love and the concern. At the same time it is entertaining. Some people misjudge stereotype. Both versions, what they did, didn't go against any of my original ideas. I'm happy about this. Especially the breakthrough is that R&H decided that we have to use Asians play Asian. Lia: Can you comment on what the critics had to say? C.Y. Lee: The Los Angeles tryout-all the critics gave it raving reviews. That's why the investors were bold enough to invest for the Broadway production because it cost a lot to mount a show in the Broadway production. But the Broadway production this time the New York Times gave it a very negative review. They didn't like it. The other review is a lukewarm review. I understand this. Any show, that's entertaining, they don't want to praise it. Usually the reviewers are looking for depth in a show. If it is too entertaining, that's not very deep. This show is very entertaining and they get a lot of standing ovations, a lot of laughs, and a lot of applause. So with reviews, I remember sometimes, even book reviewers, they have to criticize the books a little deep in order to show their own depth. When it is too entertaining, that's shallow; they regard it as too shallow. They don't want to praise it. A lot of people don't follow the reviewers. After all going to theater to be entertained, not to be educated. But the reviewers think that it should be educational.

Lia: What have you been doing while you've been in town? C.Y. Lee: Yesterday I met Fay Chew Matsuda, the executive director of The Museum of the Chinese in the Americas (MoCA). I told her I wrote two more books about early Chinese in this country. One is Days of Tong Wars. She never heard of it. That's why some of my books, they didn't get much publicity on the Chinese People. I wrote another book Land of the Golden Mountain. It's about a Chinese girl coming to this country disguised as a little boy and her experience through the gold rush days. The Tong Wars, I did a lot of research in Sacramento Library based on the Old Newspapers, I wrote this book. It's twelve stories, factual stories of Chinese Tong Wars. You know Tong wars in those days, they solved their own problems for their own protection and some mainstream writers wrote them as hatchet men. Western writers wrote them as hatchet men. Edward G. Robinson played a hatchet man. So they gave the general public a very bad image-Chinese are always secretive, hiding hatchet, knives, looking, smiling, and looking to stab you in the back through hatchet. That sort of thing. So it is a wrong impression. My second novel, Lover's Point is also a New York Times bestseller and is all about romance. This book was translated into Chinese years and years ago. I was briefly working for an Army language school as a Mandarin instructor. My office roommate is few years older than I was. He fell in love with a Japanese waitress in a city called Monterey. A lot of men, instructors, students in the army, lieutenant, corporals, and very few ladies. So suddenly there's a Japanese waitress, fairly good looking so we went to the place not to eat Japanese food, but to watch the lady, coming back and forth, swinging her little hips. There's tremendous attraction to these bachelors. I wrote a novel about her. I discovered my friend fell in love with her but is very shy and didn't really chase her. It was a sort of one-sided romance. I discovered she has two other boyfriends; one is a lieutenant, an American white guy. The other is a rich man from San Francisco; the third is an owner of a restaurant. Three guys, I immediately thought it would make a good book! She was torn three ways, one way my friend really loves her very much, emotionally, if she married my friend, she would emotionally be very secure. This man was deeply in love with her. Then there is financial security. That's the second one, the San Francisco restaurant owner. The third is physical because this is a good looking white guy. So I invented the story of being torn three ways. Lia: Do you like New York? C.Y. Lee: When I walk from here to Chinatown through the streets, it reminded me of the very old days in San Francisco Chinatown and it came back and also some of the areas in New York gave me the impression, it's almost like a foreign country. I lived in San Gabriel for 5 years, in Little China. I lived in Alhambra, Monterey Park, almost totally Chinese now. You go to the street, faces are all Asian. Every day you eat Chinese food. You speak Chinese language. As a result, my English has been deteriorating. My accent came back. Grammar went haywire! Lia: Are you working on projects now? C.Y. Lee: The Enlightening Noah Publishing Co. in Santa Clara, CA has published my other ten novels in Chinese. I just finished my memoirs. A Chinese magazine bought my memoirs. The first installment is due out in October. They are going to publish 10 installments and then it will be published as a book. Eventually, it will come out as an English edition too. |

||||

|

|

| |

|||

|

|

|

|

| | About Us | Disclaimers and Legal Information | Advertise With Us | We welcome your comments. Send e-mail to us at info@asianconnections.com Copyright ©1999-2002 AsianConnections.com |

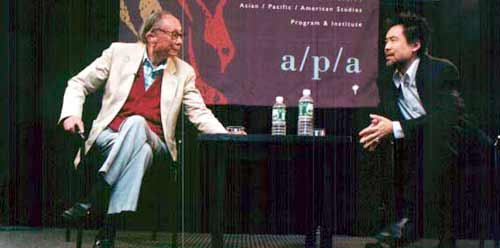

AsianConnections Arts & Entertainment Editor Lia Chang (left) currently appears as Nurse Chang on As The World Turns and One Life to Live. She is an accomplished stage, screen and TV actress, photographer and writer based in New York City. AsianConnections wishes to thank Lia and C.Y. Lee for

their generous time and efforts in making this interview possible.

AsianConnections Arts & Entertainment Editor Lia Chang (left) currently appears as Nurse Chang on As The World Turns and One Life to Live. She is an accomplished stage, screen and TV actress, photographer and writer based in New York City. AsianConnections wishes to thank Lia and C.Y. Lee for

their generous time and efforts in making this interview possible.